DISCUSSIONS

Exertion of force – Our first choice is always trying our best to navigate some else’s aggression by diverting it and using all possible effortless methods assessable at the moment. However, there are always that one in a hundred individual that don’t know when to stop and you have to apply force. Right now is just the start of a whole series of discussion related to this topic and we start with the most simple technique of a push. Common mistakes:

- Leaning into the push thinking that adding body weight adds to the push – when you lean-in and tense up your body, you actually halved the weight of your body. The tension of the body converts the system into that of a hand-dolly.

- Tensing up the entire body as the means to provide power.

- Body doesn’t work together as a unit, causing leakages.

- Directing power into the aggressor’s support leg

SCENARIOS

We went through most of the one or two handed grips. We try to match people with different partners so that they understand the need to adapt. The following questions were raised:

- How to manage distance? Seems like when someone grab and pull, the techniques don’t seem to work.

- What can you do if the other person turn in the same direction as you?

- What is meant by “the power leaked away”?

How to manage distance? If the aggressor grab and then pulled and walk away, most people’s instinct is to tense up and resist. However, if you walk in the same direction matching his steps, you can maintain the same distance. Then, the techniques that you learned in stationary pose will work.

What if the other person go in the same direction as you, neutralizing the crowbar? – When you learn the technique, you are the one who is moving to get out from the grab. If the aggressor move in the same direction as you, all you have to do is to stop rotating or go the opposite direction. Remember the technique’s key requirement is that you need to change the relative angles between the arms of the aggressor and you. Of course, one of the option is for you to move. However, it will work just fine if “the mive” is initiated by him to while you stay static. Similarly, or if both move in the opposite direction, the prying effect is retained.

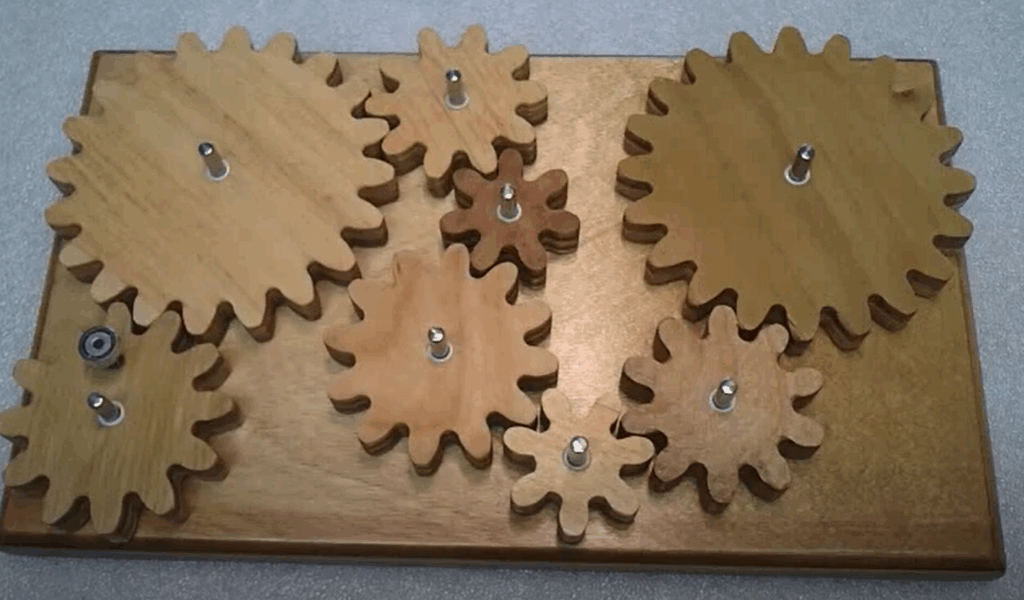

What is meant by “the power leaked away”? – the human body consists of many parts. Delivering power from one end of the body to another requires tight cooperation between all parts of the powertrain. Failure of any of those parts to connect properly will cause a huge lose of power. We call that “leakage” just like a leak of a pressure cooker.

EXERCISES

We identify the major muscle groups that power the stride. Furthermore, we added active action of the leading leg to help improve explosiveness to the move.